Rowayton Historical Society Museum

Rowayton has a rich history of being the place that everyone escaped to. In its heyday, the Roton Point area served as a steamship terminal

Find out about the places only locals are familiar with. Visit little known hideouts and avenues that open the mind into what being a local is all about.

Home > HISTORICAL NORWALK

Author of Discover Norwalk, Guide.

The official story is that Roger Ludlow settled in Norwalk in 1640, after trading some trinkets to the local Indians. The real story is much messier. In the paleo years, New England was covered by a vast ice sheet, kinda like the one depicted in The Day After Tomorrow. The ice sheet, more powerful than a monster bulldozer, crushed rocks, boulders, and soil, creating a fertile valley of muck and stuff along the main glacial stream we call the Norwalk River.

The muck proved to be good fertile ground for shellfish, finfish and GoFish. Which is what early settlers did, following the native Indian tribes who harvested clams and oysters and named most of the area.

Norwalk is an old inhabited site. Indians ruled the land (ecologically) long before the Dutch and Puritans battled it all out to pave way for our urban sprawl. Indian troubles, meaning attacks, were common in the early years, but soon peace came by way of real estate sales thanks to The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut which spawned an organizing government, and good old Roger Ludlow became one powerful dude. Until about 1662, when King Charles back in Merrie Olde England figured out what these early Nutmeggers were up to and re-established just who was in charge, the King and British Parliament.

Though there were many tribes of Indians who populated the coasts of present Connecticut and New York, the largest group in Norwalk lived in what is now Wilson Point, in a village called Naramake. In what can only be described as early zoning troubles, friction developed as a result of all the land sales between various Indian groups and the European settlers, and much of the early years was a series of fights over setbacks and boundaries. In 1650, The Ludlow Code established the concept of trespassing on English plantations, and Norwalk’s official boundaries were established from the Five Mile River to the Saugatuck River, which means that Darien, Westport, Wilton, and New Canaan were once Norwalk!

Connecticut’s 14th Governor (1754-1766) came from Norwalk. Fitch governed during a time that offers some insight into the prevailing winds that led to the Revolutionary War. To set the stage, the British were looking to recover costs of waging the French & Indian War, and in 1763 the British parliament imposed a “Stamp Tax” which was essentially a tax on every transaction in the colonies to pay for that war. This naturally didn’t sit well with the colonists and had more to do with fomenting the Revolution than the Boston Tea Party.

Fitch sent a Connecticut delegation to the Stamp Act Congress in New York City. This was widely viewed as a sell-out even though only 5 legislative votes opposed going. An effigy of Fitch was promptly burned in Hartford in protest. Tempers flared, and the first appointed tax collector was forced to resign. Significantly, while many signed a petition to appeal the Stamp Act Tax, Norwalk’s merchants were not among them. Fitch eventually came around somewhat to the colonist position, claiming he couldn’t enforce the Stamp Act Tax because he lacked paper and a collector, but the blame for supporting the English proved to be his downfall ending his time as Governor.

18th century Norwalk was a hub of agricultural enterprise. Beef, pork, cheese, butter, and hides were brought to Norwalk’s merchants. Flaxseed was shipped to Ireland and hemp was grown. The Wharf at Fort Point was home to ships that plied trade to places like Antigua and Barbados. Other private wharves were built making Norwalk one busy harbor. But there was a problem.

The Norwalk harbor could only handle ships in the 30-40 ton range. New Haven’s Long Wharf could handle 300-ton ships, making it the go-to harbor. That part of Connecticut became the administrative center for the British placing New London’s customs house as “the customs house.” This required ships from New York to go up the coast and back, a detour, in order to deliver goods to Norwalk.

While on the surface Norwalk wasn’t blatantly opposing British attempts at tightening up customs collections, under the cover of fog and darkness Norwalk was home to rebellious activity. Norwalk’s geography lent itself to smuggling with its many harbors, rivers and creeks. Norwalk also had a prominent merchant who also doubled as a customs house certificate forger– John Cannon who worked with his brother in-law John Pintard.

By 1770, most of Connecticut was rebelling in some way against the British tax policies. Yet when in September of 1774, most towns had adopted resolutions supporting the Continental Congress, Norwalk dawdled. It’s an estimate, of course, but at least 35% of the population of Norwalk and the rest of Fairfield County were British loyalists. This meant that Revolutionary fervor, once the shot heard ‘round the world kicked off, wasn’t as deeply rooted in Norwalk life as much as it was elsewhere. Which makes what happens next somewhat surprising.

Every Norwalk schoolchild knows the dates of July 11 and 12th, 1779, when a British Expeditionary army, led by British Major General William Tyron proceeded to burn Norwalk to the ground. The event catalyzed General George Washington to use the, er, inflaming story to rally his troops. Nothing beats New England folklore like a ripping yarn of Revolutionary daring-do. Norwalk though doesn’t deliver a midnight ride or a George Washington battle to commemorate. We get the burning story. To make a point, the British decided to raid coastal towns from their Long Island encampments. They picked on Norwalk because the British assumed that Norwalk supplied food and clothing to the Colonial Rebels. But much of Norwalk was sort of ambivalent about breaking free of Mother England.

As a merchant town, the wants and needs of its farmers and industrialists were more aligned to transactions. In fact, the Declaration of Independence wasn’t even celebrated in Norwalk until quite a few years after the War of Independence ended.

The raid on the town of Fairfield should have tipped off Norwalkers to the British strategy of burning everything in sight. Over 130 homes, 40 shops, 100 barns, 5 ships, 2 churches, and 4 mills were burned to the ground. As it happens, at least six buildings managed to survive the burning, but the devastation to Norwalk was significant enough to have been the catalyst for George Washington to rally support for the rebels in a letter sent round the colonies.

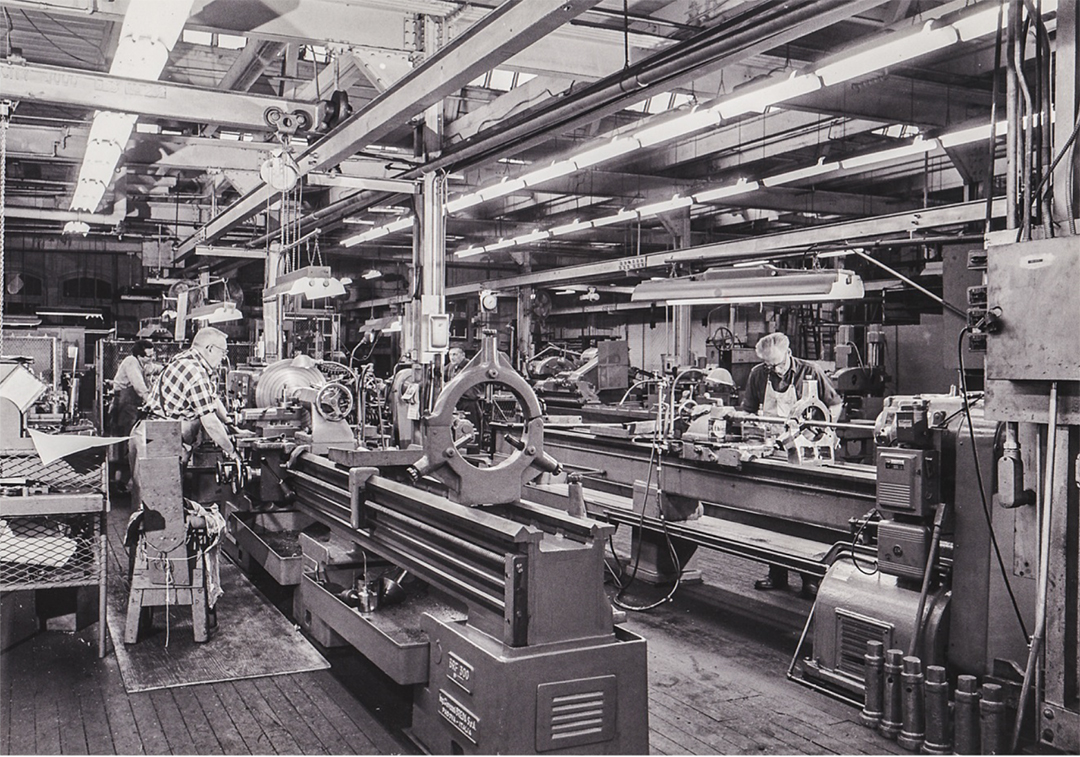

By 1800, Norwalk, like most of Fairfield County was losing farmers partly due to the post-war economic hardships, and partly due to the same issues we face today—land was expensive. Not helping matters was the Federalist form of taxation; farmland was taxed, but not other forms of wealth like stocks. This opened the way for Norwalk to build an industrial base. Norwalk became home to some significant ground-breaking manufacturing industries.

The Lockwood rolling and slitting mill was located on what is today Glover Ave, then located between the Norwalk River and the Danbury-Norwalk turnpike. High-grade iron ore was fired and converted to sheets, plates, bars, hoops, and rods at a rolling mill. A slitting mill takes the rolled iron and cuts and stamps it into nails, hoes, or leaf springs. Lockwood did both in one place, in post-colonial America the rolling and slitting mills were often miles apart.

The Norwalk Lock Company (1856) was located in South Norwalk, presently called the Lock Building, and introduced the concept of assembly lines to lock making. Nearby Yale Locks had better technology, but Norwalk Locks achieved some measure of fame in the state of Michigan, which used the Norwalk Locks in state prisons, hospitals, and almshouses.

Also in South Norwalk was the Morrison & Hoyt Shirt Factory, which employed at one time over 300 women between the ages 18-22, creating a demand for reputable housing. The R & G Corset Factory (1901) employed over a thousand workers almost all women. This bustling industry also led to South Norwalk being a key rail stop along the way to Boston and also a ripe setting for labor strife.

South Norwalk made national news over the hat industry strikes, sparking a union movement that spread rapidly. Another event, the 1853 Boston Express tragedy, triggered national interest. On May 3rd the Express reached Norwalk 8 minutes late. The train engineer sped through South Norwalk at 20 miles per hour and rounded the curve leading to the drawbridge, but the drawbridge was open.

The engine and 5 cars plunged into the Norwalk River killing 45 and seriously injuring 25. This lead to a move to standardized time-synchronized between cities and uniform timetables.

The history of Norwalk also includes bits that have been lost but not forgotten. Chief among the more interesting stories is the what ever happened to Grumman Hill, story.

The monument, at the summit of Grumman’s Hill, marks the location where Maj. Gen. William Tryon witnessed the burning of Norwalk by the British troops under his command during the engagement of July 11, & 12, 1779. There’s a monument at the site, erected by the Norwalk Chapter D.A.R. in 1904. But where’s the summit? The actual summit was razed in the 1950s so that the Norwalk Inn could be built. The plaque, affixed to a boulder, now stands in front of the driveway of the Inn.

For a few years around 1964, Norwalk was home to a 67,000 item collection of rare science books and documents, all owned by a mechanical engineer named Bern Dibner. The collection’s intricate library building has long since been replaced by a Staples on Richards Ave. But for a time these world-famous artifacts including some Leonardo DaVinci papers, publications, letters, and manuscripts by Albert Einstein and all of Louis Pasteur’s major works were part of this science research library. In 1974 Dibner sent more than 11,000 rare books, manuscripts, and other items to the Smithsonian to form the core of a national research library.

Rowayton has a rich history of being the place that everyone escaped to. In its heyday, the Roton Point area served as a steamship terminal

While the Silvermine Arts Center is technically located in New Canaan, the Silvermine the neighborhood straddles the Norwalk, Wilton, and New Canaan borders. This speaks

Just north of I-95 and on the northern boundary of South Norwalk lies the Lockwood-Mathews Mansion, one of Norwalk’s iconic attractions. Built in 1868, during a period

Most museums tend to stay put, but in Norwalk, history has been on the move. Once housed in the former South Norwalk City Hall, the