Historic SoNo

By Tod Bryant

Hat making and oystering were the major industries in South Norwalk in the middle of the 19th century.

The town did not have the abundant water power that had been the basis of rapid industrial growth in some other Connecticut towns, so its factories relied mostly on hand work and the maritime trades. Much of this industry was located in South Norwalk near the harbor and the mouth of the Norwalk River.

In 1856, a group of prominent local businessmen led by Ebenezer Hill formed the Norwalk Lock Company with Henry H. Elwell, who owned a patent for plating cast iron keys. They took advantage of the emerging technology of coal power to build their factory and foundry on Marshal Street in South Norwalk in a location convenient to both rail and water transportation. They manufactured many types of locks and keys along with doorknobs, door hardware and apple paring machines.

Norwalk Lock Company

Near the end of the Civil War, the owners of the Norwalk Lock Company, perhaps responding to the threat of Yale and Towne’s pin tumbler lock with its smaller key and more secure mechanism, saw an opportunity to start a related business nearby. They purchased the Dwight Company which had been manufacturing steam pumps in South Norwalk since 1860. Dwight’s pumps had become obsolete by 1864, so he sold the company and its factory to a group headed by Ebenezer Hill for $300,000.

They renamed the company Norwalk Iron Works, improved the steam pump design and began production of steam engines, vacuum pumps, friction hoist engines and other machinery. Expanded production required a larger facility and the company moved to North Water Street on the west bank of the Norwalk River in 1868.

The new company had a capital of $300,000 and they expected to employ about 400 men. By 1885 the company’s foundry and machine shop occupied the entire block between Water Street and the Norwalk River from Marshall Street to the railroad tracks. Most of its e buildings remain on that site in 2013 and they are now the core of the Maritime Aquarium complex.

The Norwalk Iron Works

Norwalk Iron Works became a leader in compressor technology by manufacturing products based on patents granted to Ebenezer Hill and his son, Ebenezer Hill, Jr. The most significant of these Norwalk Company Building 20 North Water Street Norwalk, Connecticut were: a patent granted on January 4, 1876 to Ebenezer Hill, Jr. for a one stage double acting air compressor and a patent the world’s first multiple stage air compressor Issued to him on July 12, 1881.

These and other advances in compressor technology made the company one of the leaders of the industry. They were able to produce air compressors of such high capacity (5000 Psig) in 1885, that the US Navy used Norwalk Company compressors to test a ship-mounted gun that would fire shells with compressed air. An international commission meeting in London in 1891 awarded the Company first Prize of $1000. The committee’s report stated that the award was presented because the Norwalk compressor was the most advanced in the world.

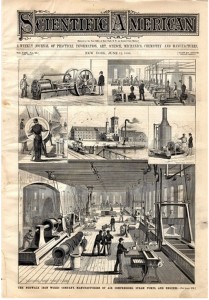

A Norwalk Company catalog published in 1888 stated their compressor producing a pressure of 5000 pounds per square inch, “…is, we believe, the highest air pressure ever attained by any practical commercial machine.” The Norwalk Iron Works was considered so innovative that it was featured on the cover of the June 12, 1880 issue of Scientific American.

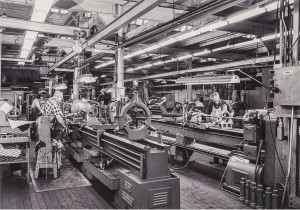

At the beginning of the twentieth century, South Norwalk had become a center of industry and one publication called it, “…a commendable and exceptional example of the true spirit of progress.” The Norwalk Iron Works was the largest manufacturing business in all of Norwalk in 1901. It employed three hundred seventy-five men and its payroll represented more than one seventh of the wages paid in the entire city. The company’s facilities included the new building (1899) at 20 North Water Street, which was described as, “…being made with especial reference to the business and … equipped with electric cranes, modern machine to0ls, and every up-to-date shop appliance.”

Compressors made in these shops were used in the world’s largest compressor site (220 million cubic feet per day) in 1906. Norwalk compressors were used widely by the US Navy for steering ships and for refrigeration. Other firms used Norwalk compressors to produce explosives. These compressors were considered so critical to the war effort that the United States government purchased the entire production of the Norwalk Iron Works during World War I.

They continued to improve their products and introduced their first direct drive compressor in 1931, their first gear reduction drive train compressor in 1939 and they were the first to produce compressors for acetylene gas. Norwalk compressors were used in many applications before World War II, including air conditioning and the compression of oxygen, hydrogen, boron triflouride, helium for U.S. Air Service dirigibles and even Nitrous Oxide (laughing gas) for the dental profession. Norwalk Company Building 20 North Water Street Norwalk, Connecticut.

In 1922, the Norwalk Iron Works merged with The Carbonic Machine Company of Peoria, Illinois, which also made gas compressors. The new company continued its operations in Norwalk and Charles J. Norwalk Company Building 20 North Water Street Norwalk, Connecticut.

Thompson, President of the Iron Works became the head of the merged business. The prosperity of the both South Norwalk and the Norwalk Iron Works came to an end in the Great Depression when the company went into receivership in 1938. The original foundry and machine shop buildings were sold. The new company, now called The Norwalk Company, consolidated all of its operations in the 20 North Water Street building at that time.

The United States government once again called on the Norwalk Company to supply compressors in wartime. During World War II, the entire production of the company was used for the war effort and between 1941 and 1945 the company manufactured an average of one hundred eighty five compressors per year for a total production of nine hundred thirty-seven units. The company was awarded the Army-Navy “E” (for Excellence) flag with four stars for their consistent on-time delivery and a record of no rejections. The award was presented by Admiral William C. Watts at a large outdoor event in front of the North Water Street building in 1942.

The Norwalk Company continued to build innovative new products after World War II. They included a vertical configured compressor and a hydrogen gas booster compressor to 20,000 Psig in 1946; several specialized compressors for university research; a non-lubricated gas compressor in 1950 and a compressor designed to be used with radioactive gas. The company produced several types of compressors aimed at specific markets, including compressors used in fueling of natural gas powered vehicles, during the last quarter of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century.

Ownership of the Norwalk Company changed several times in the mid-twentieth century. In 1968 the company was sold by Richard Steele and Associates to the Union Corporation, which enlarged the 20 North Water Street building with a 15,000 square foot addition in 1977 to accommodate increased production. The Union Corporation shifted its corporate focus away from manufacturing and, in 1984, it sold the company to the private interests who still own it in 2013. In 2004, the company sold the 20 North Water Street building to North Water Street, LLC, which sold it to Tarragon, LLC in 2007. In 2009, ownership of the property was transferred back to North Water Street, LLC, which owns it in 2013. The company has been renamed The Norwalk Compressor Company and it has moved its operations to Stratford, Connecticut where it continues to manufacture compressors in 2013. The North Water Street building was demolished in July of 2012.

Architecture

The Norwalk Company Building is a typical example of a late nineteenth century heavy manufacturing facility. The elements of its construction and methods of manufacture had been evolving for over half a century. Its steel frame construction, brick curtain walls, saw tooth roof, overhead cranes, individually powered machines and separate pattern storage facility followed the best industry practices of the time.

Early factory buildings were usually not purpose-built, so the manufacturing process had to adapt to the existing building. This practice was not always efficient and by the middle of nineteenth century, engineers and architects began to design factories specifically for the most effective handling of materials and the best use of space and light in the manufacturing process. The textile industry led the way in these efforts and the long, narrow mill building was developed to make the most efficient use of light and air.

By the late nineteenth century, designers looked to the mechanical efficiencies of the machine as a metaphor for their new vision of a factory with efficient materials handling. Some designers even considered the workers to be moving parts in the factory as “master machine”. The Norwalk Company Building uses the “technical triumvirate” of late nineteenth century industry: electric drive, a powered crane and steel construction, to create an efficient “master machine” for the manufacture of compressors.

Design

The steel industry developed very large buildings needed to accommodate new machinery, such as overhead cranes, that were needed in their production process. By the 1870s, a form known as the production shed had evolved that was adopted by many industries with similar production needs. It was a simple architectural form with high ceilings and vast open spaces which allowed for the orderly progression of the manufacturing process. The Norwalk Company building is a production shed with a flat roof to accommodate an overhead crane combined with a machine shop which uses a saw tooth roof to provide a well-lit interior. It has been connected to a smaller accessory building of simple, functional design to form one structure..

Power

The city of South Norwalk was established as a separate political entity within the Town of Norwalk in 1871 and by 1892 it had its own city-owned electrical plant which supplied power for street lamps and industry. 43 The Norwalk Iron Works’ original plant had been powered by coal with a central power source and it needed a series of overhead shafts, pulleys and belts to drive individual machines as shown in the Scientific American cover illustrations from 1880

The new building took advantage of South Norwalk’s electricity to power individual machines. This innovation allowed the building, like others of that time, to be designed as a large production shed without the use of overhead power sources. Individually-powered machines also allowed for better integration of the manufacturing process, which led to more open shops. In 1896, industrial journalist Horace Arnold toured several American factories and wrote a series of four articles for Engineering magazine, reporting on and evaluating their design, construction and management. He found that the best of them were built using the same elements that are combined in the Norwalk Company Building, including: large windows, an open machine bay with a saw tooth roof, large single-story rectangular building with few partitions and a traveling electric crane.

Overhead Crane

The electric crane revolutionized manufacturing. Electric power allowed for the use of an overhead crane in the production shed and machine shop sections of the building. Steam powered cranes had been developed in England in the 1840s, but they were not used in the United States until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The first electric powered overhead crane in the United States was installed in the E. P. Allis Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1888.47 By 1896, some industries had discovered that the overhead crane was best used to move materials around, rather than simply lifting heavy objects.48 The Norwalk Company used several overhead cranes of different sizes. There is a large one which spans the full width of the main production shed and travels almost its entire length. It was used for moving completed machines weighing as much as XXX tons. Smaller cranes were used to move subassemblies in production shed and the machine shop area.

Structure

Structural steel transformed American industrial buildings.50 By the end of the nineteenth century industrial buildings were often constructed, like the Norwalk Company building was, with steel frames, brick curtain walls and a steel truss system to support the roof (Photos 14-19).51 The wood frame construction used in most of the nineteenth century had limited strength and it was not fire proof. Frames constructed of built-up steel girders, like those used in the Norwalk Company Building, provided uniform quality and standardized forms. Steel structural elements could be consistently specified for strength and dimension and they could be accurately placed in the plan. Steel construction was faster and lighter than previous methods and its components were smaller, which yielded more usable space. The Norwalk Company Building contains several examples of columns and other structural elements that were built up and riveted together using plates, angles and webs. This was a common practice at the time and some engineers developed their own version of these structural elements. The steel structure supported a massive open work floor which allowed for an integrated and economical workflow.

Wood structure was used for the saw tooth roof, even though it sits on a steel frame. It was probably less expensive and possibly lighter to construct the complex structure required for this roof form in wood. The smaller pattern storage/machine shop building was built with a more traditional heavy timber frame with brick walls.

The 1977 addition is also a vast, undivided space. It is built with load-bearing concrete block with a flat, corrugated metal roof, but its internal structure is similar to the form of the older building. It also uses steel columns with a steel truss system to support the roof, but both of these elements are much lighter than those used in the 1899 building. It has fewer, smaller windows, since it was built to be illuminated by florescent lighting. This section of the building also has no external ornament of any kind. It is an unadorned industrial box, typical of its era of construction.

Exterior

The Norwalk Company Building presents an impressive façade on North Water Street. The façade remained substantially unchanged since its construction except for the elimination of the office entrance seen in a c.1953 photograph.

Companies often used the design of their buildings to present their best face to the public.53 They intended the design of the building to express, “…strength, stability and function, rather than picturesque or formal considerations.” The architects of the Norwalk Company Building addressed this issue by employing a design solution influenced by the Romanesque style which was used extensively in churches and public buildings, as well as factories, in the last half of the nineteenth century.

Their design uses ten identical bays anchored by piers at the ends of the building and divided by similar piers supporting an unbroken entablature to create a rhythmic and pleasing façade. Each bay contains two identical arched windows below a corbelled table on the second story and a pair of rectangular windows of similar size on the first story. This approach allowed vertical loads to be concentrated in the piers, while also adding visual interest to the building.56 The two tiers of windows visually minimize the height of the building and, despite the fact that there is a single, very tall room inside, give it the appearance of having two stories.